This book running into 299 pages has been

edited by Batty Weerakoon with an introduction.

Sunday essay by Ajith Samaranayake - Sunday Observer Mar 7 2002

|

|

It has been one of the most piquant paradoxes of post-Independence politics that the staunchest exponents of the parliamentary system and its stoutest upholders should have been Marxist politicians particularly of the Trotskyist sect. Dr. N. M. Perera, Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, Leslie Goonewardene, Edmund Samarakkody, Pieter Keuneman and others were not only skilled parliamentary performers but could be depended on to expound on the intricacies and niceties of parliamentary practice and etiquette at the drop of a Standing Order

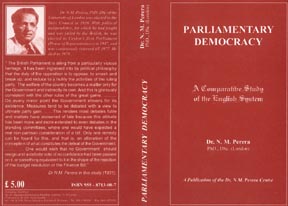

And among them the pre-eminent whose name like Abu Ben Adam's led the rest was Dr. N. M. Perera. Reading this book 'Parliamentary Democracy - a comparative study of the English system' one has no difficulty in knowing the reason.

To take this book in one's hand itself is to feel a sense of history. This is part of the doctoral thesis submitted in December 1931 by Dr. Perera for his PhD to the London University. He was to receive the DSc for a larger work on the same subject from the same university and his tutor was, of course, the legendary Harold J. Laski, one of the sharpest thinkers and writers of the British Labour Party. Dr. Perera observes that even as he was working on this thesis Hitler had come into power in Germany and the thesis indeed is a comparative study of legislature in Britain, US, Germany and Italy.

If some of the material and references here appear dated and quaint one has to keep in mind that this is the stuff of history written even as that history was unfolding before a student from a colonial country working in a great university of an imperial capital even as that imperialism had entered upon its last stage and death struggle. And it was surely no accident that this young student who so diligently expounded the quaint ceremonies of the parliamentary ritual should have played a not inconsiderable role in the final sweeping away of that imperialism from his own homeland.

The opening of Dr. Perera's introduction itself gives us an idea of the historical breadth and sonorous magisterial tone of the work. He writes:

"At a time when parliamentarism is at a serious discount, at a time when dictators are straddling over the 'corpse of liberty', and at a time when pinchbeck Mussolinis are cropping up here, there and everywhere, it seems more than courageous to postulate the continuance of democratic institutions. Apparently democracy has failed; it has run its course.

In the cycle of human institutions the stage of democracy has been reached and is now passing; and we must inevitably proceed to the next stage of dictatorship. This simple mechanistic theory however plausible is not very convincing. A crude generalisation of superficialities, it neither represents a close analysis of existing facts nor a grasp of history.

Such facile generalisations might delude the multitude and may themselves help depress the stock of democracy. Their constant loud-mouthed reiteration may excite latent psychological reactions which would generate a miasma of dull prejudice fatal to a balanced judgement. But they cannot stand the instructed scrutiny of a thinking person; they will crumple before the searchlight of historical facts."

The bulk of this book constitutes an exhaustive and closely-argued exposition of the role of the Speaker and Deputy Speaker in Parliament, Questions in the House, Public Bills and Finance Bills. This should be required reading for all parliamentarians and now that the N. M. Perera Centre under Mr. N. S. C. Perera has taken such pains to bring out this book it should occupy a special place in the parliament library which sadly a new generation of parliamentarians seems to be treating more as a mausoleum rather than a live and active place.

Of course to read Dr. Perera's book is to realise how much we have regressed from the ideal. Today the Mother of Parliaments in Britain is not even a 'talking shop', the pejorative role traditionally assigned to it. Prime Minister Tony Blair hardly attends the House except at Prime Minister's Question time and the rigid control exerted by the Whips has led to the stifling of any vigorous debate. In Sri Lanka itself Parliament exists uneasily in the Leviathan shadow of the Executive Presidency and it is left to be seen what impact such innovations as the return to the Executive Committee system which has been proposed by the UNF Government will have on the rejuvenation of Parliament.

Dr. Perera is strongly mindful of the fact that if it is to be effective, parliamentary democracy will have to serve the needs of the people at large. It is interesting that after examining the case for dictatorship, both of the fascist and communist varieties, he should dismiss their claims although he does see some merit in the latter. But finally it is for democracy that he plumps arguing that 'there is no finality about political democracy. It is the glory of the democratic state that the institutions can be continuously adapted to suit the fluctuating structure of the society.

The problem of democracy is indeed the problem of institutions. ...In Parliament we have such an institution. But it would be a mistake to assume that the form and shape of a Parliament that satisfied Victorian conditions would serve the twentieth century.'

Here then is the crux of the matter. How do we fashion Parliament into an institution which serves the needs of a society which has not only shed its Victorian skin but now worships at the temple where the presiding deities are neo-capitalism and digital technology? Of what relevance is Parliament in the epoch of the global market and the Internet? Can the re-introduction of the Executive Committee system, which Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike is said to have favoured, rejuvenate Parliament? Or should not we rather give more importance to the already-existing committee system for the scrutiny of public and finance bills including the budget as Dr. Perera advocates here? Incidentally reading this book one understands why the LSSP opted for the parliamentary rather than the revolutionary path.

They genuinely believed, if rather naively that Parliament itself could be fashioned into a popular instrument of the mass will. It was not for nothing after all that it has been said that Dr. N. M. Perera would have made an ideal Labour Prime Minister of Britain.