Geoffrey Bawa

BAWA GEOFFREY of “Lunuganga”,

Dedduwa, died on the morning of 27th May 2003. Cremation will take place at

“Lunuganga” Dedduwa on 28th May, Wednesday at 5.30 p.m. “Lunuganga”,

Dedduwa, Bentota. No flowers please.

Lanka's master builder is dead

Architect Geoffrey Bawa, one of the master

builders of modern Sri Lanka and a man whose monumental brilliance will be

remembered for ages in the new House of Parliament, died yesterday at the age of

84.

His biographer Brian Brace Taylor

described Geoffrey Bawa as one of the supreme examples of an architect for our

times: fully conversant with contemporary technology and international

developments, but with a deep understanding - and feeling for -vernacular

traditions.

"Highly personal in his approach, evoking

the pleasures of the senses that go hand in hand with climate, landscape and

culture, Bawa brings together an appreciation of the Western humanist tradition

in architecture with local needs and lifestyles," the author said.

Besides the majestic Parliament building

on the banks of the Diyawanna Oya, Geoffrey Bawa designed the award winning

Kandalama hotel the Bentota Beach and Blue Waters hotel and Lighthouse down

South among scores of other well know works of art in Architecture.

Geoffrey Bawa was widely known and admired

as Sri Lanka's most prolific and influential architect. His work has had

tremendous impact upon architecture throughout Asia and is unanimously acclaimed

by connoisseurs of architecture worldwide. Although Mr. Bawa came to practice at

the age of 38, his buildings over the last 25 or more years are widely acclaimed

in Sri Lanka. The intense devotion he brought to composing his architecture in

an intimate relationship with nature is witnessed by his attention to landscape

and vegetation, the crucial setting for his architecture. His sensitivity to

environment is reflected in his careful attention to the sequencing of space,

the creation of vistas, courtyards, and walkways, the use of materials and

treatment of details.

Mr. Bawa was born in 1919 in what was then

the British colony of Ceylon. His father was a wealthy and successful lawyer, of

Muslim and English parentage, while his mother was of mixed German, Scottish and

Sinhalese descent. In 1938 he went to Cambridge to read English, before studying

law in London, where he was called to the Bar in 1944. After World War II he

joined a Colombo law firm, but he soon tired of the legal profession and in 1946

set off on two years of travel that took him through the Far East, across the

United States and finally to Europe.

Bawa qualified as an architect in 1957 at

the age of thirty-eight and returned to Ceylon. Bawa's growing prestige was

recognized in 1979, when he was invited by President Jayewardene to design Sri

Lanka's new Parliament at Kotte. At Bawa's suggestion the swampy site was

dredged to create an island at the centre of a vast artificial lake, with the

Parliament building appearing as an asymmetric composition of copper roofs

floating above a series of terraces rising out of the water. Abstract references

to traditional Sri Lankan and South Indian architecture were incorporated within

a Modernist framework to create a powerful image of democracy, cultural harmony,

continuity and progress and a sense of gentle monumentality.

Although it might be thought that his

buildings have had no direct impact on the lives of ordinary people, Mr. Bawa

has exerted a defining influence on the emerging architecture of independent Sri

Lanka and on successive generations of younger architects. His ideas have spread

across the island, providing a bridge between the past and the future, a mirror

in which ordinary people can obtain a clearer image of their own evolving

culture.

The cremation will take place at his

Lunuganga residence in Dedduwa, Bentota at 5. 30 p.m. today.

Daily News Thu May 29 2003

Geoffrey Bawa is no more

by Karel Roberts Ratnaweera

Sri Lanka's internationally recognised

architect, Geoffrey Bawa is no more. He passed away on Tuesday morniing and was

cremated at Lunuganga, Dedduwa, Bentota, on his private estate.

Geoffrey Manning Bawa and his elder

brother Bevis were the only two children of Justice Bawa. Their mother was a

member of the well-known Dutch Burgher Family of Schrader, from Negombo.

Born in 1919 and educated at Royal

College, he then went to England and read Law at Cambridge. Called to the Bar

from the Inner Temple,Bawa spent several years living abroad before returning to

the island where he practised Law as Junior to Justice E.F.N.Gratiaen. But he

abandoned Law for Architecture in which he obtained the highest degree from the

Royal Institute of Architects of Great Britain, and from the American Institute

of Artchitects as well.

A well-known Colombo figure, he would

drive his Silver Cloud Rolls-Royce down Galle Road, attracting much attention as

he drove down South or back to Colombo. The highpoint of his distinguished

career was when he was asked to design and build the new Parliamentery complex

on the Diyawanna Oya in Kotte.

He told this writer in an interview that

he had designed the vast complex using ancient Sinhala artchitectural tyles as a

guideline. Bawa also designed and built the Bentota Beach Hotel, the first hotel

to be designed by him, and one of the first hotels in the South. He also

designed and built Kandalama Hotel according to his unique sense of design

applied to the climate and terrain.

Geoffrey Bawa had been ailing for some

years but that did not prevent him from going to good concerts of Western

Classical Music, being wheeled into the hall in his wheelchair. He was an

aesthete who abhorred anything that was less than aesthetically pleasing, and he

applied these high standards in his work.

Geoffrey Bawa's brother Bevis, also lived

in Bentota and predeceased him some years ago.

For all his talent and sophistication in

personal style, he was a shy man and dreaded newspaper interviews.

Geoffrey Bawa's Colombo residence, also

reflecting his architectural styles, was in Inner Bagatalle Road, Colombo 03.

Island Features - Sun Jun 1 2003

Geoffrey Bawa: a valediction for a

colossus

by

Neville Weereratne

by

Neville Weereratne

What would be the surest method of assessing a person’s life and

contribution? Sheer volume would possibly be one very tangible measure rather

than quality which would be an arbitrary judgement but on both counts, Geoffrey

Bawa would stand out as the single, most comprehensive colossus.

His achievements have

recently been chronicled in a book appositely called Bawa: The Complete Works

(David Robson: Thames & Hudson, London). It is an appropriate title since there

seemed no prospect whatever that Geoffrey would work again after the disastrous

stroke he suffered in March 1998. In the several years that followed, many

people, friends, domestics, colleagues, medical staff have nursed him with

enormous affection. His death last week sets them all somewhat at rest. They

laboured long and assiduously for his comfort, and they did this with affection.

Geoffrey drew affection from

everyone about him because that was the single, personal quality that marked him

out. He was himself affectionate to the end. The last time we saw him was in

March this year at Lunuganga, resting in his three-wheeler under the shade of a

tree, the breeze from over the lake cool and refreshing. He had learnt to utter

a few syllables and made himself coherent. He was pleased to see us, nodding and

smiling his welcome. When we were about to leave promising to return, he was

quite sure we wouldn’t. "Ne", he repeated over and over in Sinhala. And so it

was that we didn’t see him again.

But now that we are in a

valedictory mode, we cannot escape the attempt to assess his skills as an

artist. Prof. Robson, in his book on Geoffrey’s work, neatly reveals the extent

of that achievement. This, Robson sees, as a lifetime of addiction to space and

proportion, spaces to live in and places to play and pray in, confined space and

open places; areas in which light and air, those fundaments of the good life,

could have free and easy play.

If there are any secrets in

the art of architecture as practised by Geoffrey, it was his constant effort to

co-operate with nature. If, however, nature was not always prepared to lend

itself to his purpose, Geoffrey was quite happy to bend it to his will.

He did that masterfully at

Lunuganga, his property near Bentota where he whittled away at a hill, Cinnamon

Hill he called it, until he could view the lights on a temple far off reflected

in the lake below his garden. Then he placed a huge Chinese stone jar in the

middle distance to draw all three elements into a single perspective. He

manipulated nature. He knew precisely what he was doing when he hung weights on

the branches of the araliya trees outside his house so that their limbs would

fan out, extend and become expansive patterns of flowers and foliage.

Lunuganga is a masterpiece

which, Geoffrey once said, had grown over the years, "a place of many moods, the

result of many imaginings, offering me a retreat to be alone or to fellow-feel

with friends." A lorry driver who once walked around the garden while his bricks

were being unloaded exclaimed: "But this is a very blessed place!"

The vistas Geoffrey created

at Lunuganga give infinite pleasure. Everything is in place; everything is on

perfect order and harmony.

And not only in his own home.

Geoffrey Bawa’s enormous achievement is that he carried this message, this

aesthetic - if you prefer that expression - far and wide across Sri Lanka - and

indeed, into neighbouring countries, India, Indonesia, the Maldives, Mauritius,

and even to Panama.

One of his first efforts,

even before he qualified as an architect at the Royal Institute of British

Architects in 1957, was an extension he designed for Arjun Deraniyagala in

Guildford Crescent. There already appeared the symptoms of a man pre-occupied

with space and proportion.

This inevitably meant looking

for a relationship between interior and exterior. Geoffrey would not distinguish

between them but sought to bring them together in a unity, complete and whole.

He believed that the inside and the outside were indivisible, that architecture

involved a dialogue between the interior and the landscape, between the garden

and the hearth. Traditional building, which took into account the nature of the

site that was being built upon, was an exemplar of this idea. Trees were

sacrosanct. Boulders made great sculpture.

Inexpensive local materials

Geoffrey also turned to

inexpensive local materials - brick, timber, clay tile and plaster. He also

began to use the half-round clay tile (Sinhala ulu) over corrugated cement

roofing as an effective, rain-proof covering that, at the same time, was most

attractive. Another innovation that was highly successful, once pointed out to

me as a hallmark of Geoffrey Bawa, was the use of polished coconut columns with

granite base and capital. The granite was to protect the timber from termites.

Geoffrey’s achievements have

been acknowledged by his peers in the business. The many awards he has received

are evidence enough of this: he was the recipient of a Lifetime Award from the

Aga Khan Foundation in 2001. Earlier, the highly regarded Royal Institute of

British Architects organised an exhibition of Geoffrey’s works in London which

eventually toured several other countries in 1986: Brazil, Singapore and

Australia. Geoffrey has been feted too, by the state: he was a Vidya Jothi and a

Desamanya.

Geoffrey Bawa’s background

should be recounted if only to create a perspective in which to view him. The

apocryphal story told by his brother, Bevis, of the meeting of their grandfather

and their future grandmother, a young European girl "about to be swindled by a

pseudo gem merchant" at the NOH in Galle and of their swift courtship and

marriage in an afternoon’s enterprise, has to be believed if only because it is

the stuff of which these Bawa brothers were made. It has all the elements of the

improbable but then the grandeur of Geoffrey’s imagination (and, indeed, that of

Bevis’s) is what we need to understand. They were unfettered. They enjoyed the

freedom of talent and the luxury of acceptance.

Geoffrey was thirty-one (he

was born in 1919), when, after completing a degree in English at Cambridge

University and being called to the Bar, he turned to architecture. This was to

be the beginning of a great odyssey which was to see him return to Sri Lanka,

the country of his birth which he hadn’t known before and which he was to

discover and love in quite a passionate sort of way. He learnt to appreciate the

island’s individual characters - the climate, its physical resources, its

people, the social conditions that prevailed, the culture, its ways of building,

and it was Geoffrey’s outstanding capacity to absorb these elements and to

transform them into an individual artistic statement.

On this journey of discovery,

Geoffrey was aided by Ulrik Plesner, the Danish architect who first came to Sri

Lanka in 1957 to work with Minette de Silva in Kandy and who later joined Bawa

at Edwards, Reid and Begg. Plesner had a practical turn of mind and had acquired

a particular appreciation of the local building tradition. In the partnership

that was forged between them they would have explored those facets of the

vernacular architecture that made it unique.

Geoffrey conceded that this

so-called vernacular architecture had an impact on the development of his own

philosophy. "In my personal search," he wrote in 1958, "I have always looked to

the past for the help that previous answers can give." He found this, he said,

in Anuradhapura but he was also prepared to look at the latest building

completed in Colombo. He would look for the answers he sought from Polonnaruwa

to the present day. Geoffrey referred to this great spectrum of building as "the

whole range of effort, peaks of beauty and simplicity and deep valleys of

pretension."

He was the perennial student,

interested, inquiring, but for all that very much his own man. His knew his mind

and he would press determinedly for his point of view.

Aspects of vernacular

architecture begin to emerge in the solutions he found to specific problems.

They can be seen in the parliamentary complex at Sri Jayawardenapura, Kotte, set

in an artificial lake with its cone-shaped copper-roofs rising out of the water;

the Bentota Beach Hotel which drew its form from an old Dutch star-fort; or the

granite face of the Kandalama Hotel that blended effortlessly with its rocky

background.

My personal favourite among

his 200 works or so, is the elegant house he built with Ena de Silva in Alfred

Place, Kollupitiya. It is a masterful blend of the choicest indigenous

architectural features combining with a most effective juxtaposition of spaces.

It fulfils every demand that could be made of a house which is a place to be

lived in by the several members of a family pursuing their individual interests.

It was also Geoffrey’s genius

that he recognised in those around him their particular talents and employed

them with unerring flair. So, you will see sculptures by Laki Senanayake or his

drawings embellishing an hotel, batik ceiling cloths and gigantic flags designed

by Anil Gamini Jayasuriya for Ena de Silva Batiks enlivening others, or the

handloom fabrics of Barbara Sansoni everywhere in Geoffrey’s public buildings.

I suppose it is possible to

consider every building that Geoffrey designed and built to be a permanent

monument to him and his art. That would be so if they are retained and

maintained as Geoffrey intended them. Unfortunately there appear to be

latter-day proprietors who would attempt to improve on the original, with

disastrous results. This is where something more than cursory vigilance is

called for. We cannot afford to be cavalierly about this. That responsibility

could well rest with his proteges of whom there are many and who have all

distinguished themselves.

What Geoffrey Bawa achieved

was the height of perfection insofar as that state could ever be realised. He

set standards which need to be upheld.

As I say, that responsibility

now rests with his students. There is also the Lunuganga Trust which Geoffrey

set up to provide opportunities for artists and architects. These are some of

the forces that need to be drawn upon to ensure that the memory of this colossus

will be held in due regard, that the canons of good taste he set and championed

are maintained, that the magnificent edifices he created will, with the

buildings of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, remain permanent symbols of a

pleasing, beautiful, active, resurgent, modern Sri Lanka.

Glimpse of History from

ANCL Archives:

Geoffrey Bawa - Legendary Architect and

nature lover

by Indeewara Thilakarathne - Sunday Observer Jan 28 2007

|

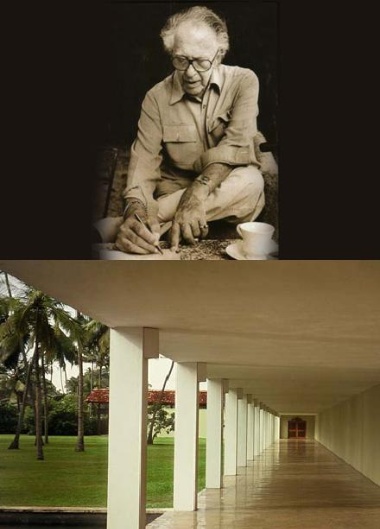

Geoffrey Bawa |

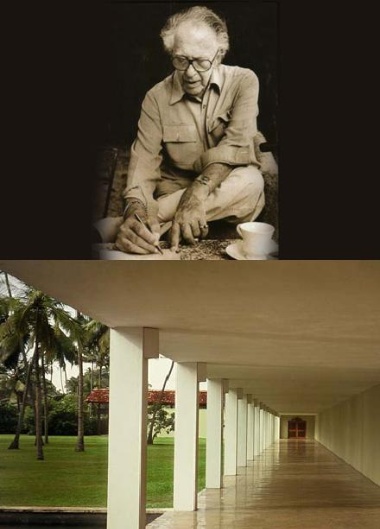

Banglow on the summit of Lunugaga estate |

The Wind-mill which sustains water supply to one of his cottages at

Lunugaga |

Urns , a facinating feature at Lunuganga |

Some of the artifacts collected by Bawa |

A typical Bawa’s living room |

One of the rare buildings at Lunuganga

|

Entrance to the Lunuganga

|

A panoramic view of Lunuganga

|

Pleasure garden at Lunuganga

|

Wall-paintings at the rear entrance to the garden |

Geoffrey Bawa (1919 - 2003) is considered

as the founder of the tradition of tropical architecture and a unique style of

architecture where life is celebrated in space and light.

Bawa's colossal influence in shaping the

form and motif of Sri Lankan architecture is well recognised and his work has

had tremendous impact upon architecture throughout Asia and is acclaimed by a

connoisseur of architecture worldwide.

With his own approach to architecture,

Bawa's tradition is unique which blends together the Western humanist tradition

in architecture exotically with the lifestyle, climate, landscape and the

traditions of Sri Lanka.

Though he started late in his career at

the age of 38, Bawa's creations over the last 25 years bear testimony to his

intense devotion to the subject and tradition he moulded in considering the

landscape, vegetation and the crucial setting for his architecture.

His concerns for environment is manifested

in sequencing of space, the creation of vistas, courtyards, and walkways, the

use of materials and treatment of details.

One of Bawa's earliest domestic buildings,

a courtyard house built in Colombo for Ena De Silva in 1961, was the first to

fuse elements of traditional Sinhalese domestic architecture with modern

concepts of open planning, manifesting that an outdoor life is viable on a tight

urban plot.

The Bentota Beach Hotel of 1968 was Sri

Lanka 's first purpose-built resort hotel. During the early 1970s a series of

buildings for government departments developed ideas for the workplace in a

tropical city, culminating in the State Mortgage Bank in Colombo hailed at the

time as one of the world's first bio-climatic high-rises.

Bawa also designed a holiday villa for the

Jayawardene family in 1997 on the cliffs of Mirissa, which demonstrates Bawa's

indefatigable inventiveness.

Bawa was born in 1919 during the British

Raj in ' Ceylon '. His father was a wealthy and successful lawyer, of Muslim and

English parentage, while his mother was of mixed German, Scottish and Sinhalese

descent.

In 1938 he went to the University of

Cambridge to read English, before studying law in London, where he was called to

the Bar in 1944.

Following World War II he joined a Colombo

law firm, but he soon tired of the legal profession and in 1946 set off on two

years of travel that took him through the Far East, across the United States and

finally to Europe.

In Italy he toyed with the idea of

settling down permanently and resolved to buy a villa overlooking Lake Garda .

He was now twenty-eight and had spent one-third of his life away from Ceylon.

He was more European in outlook and had a

loose-knit relationship with Ceylon. The plan to buy an Italian villa did not

materialize, however, and in 1948 he returned to Ceylon where he bought an

abandoned rubber estate at Lunuganga, on the south-west coast between Colombo

and Galle.

His dream was to create an Italian garden

from a tropical wilderness, but he soon found that his ideas were compromised by

a lack of technical knowledge.

In 1951 he was apprenticed to H. H Reid,

the sole surviving partner of the Colombo architectural practice Edwards, Reid

and Begg.

Following Reid's death suddenly, a year

later Bawa returned to England. After spending a year at Cambridge, he enrolled

as a student at the Architectural Association in London, where he is remembered

as the tallest, oldest and most outspoken student of his generation.

Bawa finally qualified as an architect in

1957 at the age of thirty-eight and returned to Ceylon to take over what was

left of Reid's practice. He gathered together a group of talented young

designers and artists who shared his growing interest in Ceylon 's forgotten

architectural heritage, and his ambition to develop new ways of making and

building.

As well as his immediate office colleagues

this group included the batik artist Ena de Silva, the designer Barbara Sansoni

and the artist Laki Senanayake, all of whose work figures prominently in his

buildings.

He was joined in 1959 by Ulrik Plesner, a

young Danish architect who brought with him an appreciation of Scandinavian

design and detailing, a sense of professionalism and a curiosity about Sri Lanka

's building traditions.

The duo formed a close friendship and a

symbiotic working relationship that lasted until Plesner quit the practice in

1967 to return to Europe and Bawa was joined by the engineer K. Poologasundram,

who remained his partner for the next twenty years.

Bawa's growing prestige was recognized in

1979, when he was invited by President Jayawardene to design Sri Lanka 's new

Parliament at Kotte, 8 kilometres east of Colombo .

At Bawa's suggestion the swampy site was

dredged to create an island at the centre of a vast artificial lake, with the

Parliament building appearing as an asymmetric composition of copper roofs

floating above a series of terraces rising out of the water.

Abstract references to traditional Sri

Lankan and South Indian architecture were incorporated within a Modernist

framework to create a powerful image of democracy, cultural harmony, continuity

and progress and a sense of gentle monumentality.

During the 1980s Bawa also designed the

new Ruhunu University near Matara, a project that enabled him to demonstrate his

mastery of external space and the integration of buildings in a landscape. The

result is a matrix of pavillions and courtyards, arranged with careful

casualness and a strong sense of theatre across a pair of rocky hills

overlooking the southern ocean.

These projects brought Bawa international

recognition and his work was celebrated in a Mimar monograph by Brian Brace

Taylor and in a London exhibition. A later book by Christopher Bon on Lunuganga

served both as a personal tribute to a friend and a beautiful photographic

evocation of a garden.

But the Parliament building and Ruhunu had

left Bawa exhausted and at the end of the 1980s he withdrew from his partnership

with Poologasundram and relinquished the name Edwards, Reid and Begg. He was now

seventy and it was widely assumed that he would retire to Lunuganga and

contemplate his garden.

However, the break signalled a fresh round

of creative activity and he began to work from his home in Bagatelle Road ,

Colombo , with a small group of young architects.

Together they embarked on a stream of

ambitious designs - hotels on Bali and Bintan, houses in Delhi and Ahmedabad,

and a Cloud Centre for Singapore. None of these was built but each created

enormous amounts of ideas.

Some of these ideas came to fruition in

three hotels built in Sri Lanka in the 1990s: the Kandalama, conceived as an

austere jungle palace, snaking around a rocky outcrop on the edge of an ancient

tank in the Dry Zone; the Lighthouse at Galle, defying the southern oceans from

its boulder-strewn headland; and the Blue Water, a cool pleasure pavillion set

within a sedate coconut grove on the edge of Colombo.

In 1998 Bawa was tragically struck down by

a massive stroke that left him paralysed and unable to speak. A small group of

colleagues, led by Channa Daswatte, have continued to work on the projects he

initiated before his illness - an official residence for the President, a house

in Bombay , a hotel in Panadura - with drawings being taken down the corridor

from the office to Bawa's bedroom for nods of approval or rejection.

He died in 2003.Bawa won Sri Lankan and

International awards including the national honour of Deshamanya from the

Government of Sri Lanka in 1993 and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture

Chairman's Award in 2001.

indeewara@sundayobserver.lk

‘Brief’

Garden of Eden

‘Brief’

Garden of Eden

By Rathindra Kuruwita - Nation Aug 12

2007 - http://www.nation.lk

I have heard stories about Bevis Bawa and his haven ‘Brief.’ It

has been called “a playground of the senses,” a place full of inviting nooks,

alcoves, leafy recess and cloisters. A little corner in the country that is so

tranquil, it encourages one to just lay back and take it slow.

The long winding road

Finding the place that the villagers call ‘Bawa Mahathayage

waththa’ proves to be no easy task. After the turn off from the Galle Road, the

Kaluwamodara road seems to get narrower with each curve. Although we have a map

of sorts hastily drawn by a friend we find it difficult to keep track of our

path. We have to pull into an ally to let a bus pass and have a difficult time

getting the vehicle back on to the road, without falling into the ditch lining

the path.

Finally realising that the map will not do us any good, we venture to do one of

the most difficult tasks for a man, to ask directions. The way they give

directions, enthusiastically and with smiles and the way they pronounce the name

‘Bawa Mahathaya’ tell us that he is very fondly remembered. And why shouldn’t

they, when he has distributed most of his land among the villagers, a fact that

I am to learn later.

We reach a slab of wood, which has faded ornate Gothic lettering carved deeply

and precisely into it saying ‘Brief.’ We are unaware that ahead of us is a long

winding road. We travel down yet another narrow road raised across a marsh. Half

way through we confront a motorcycle coming straight at us in full throttle,

both parties break violently and the motorcyclist nearly becomes one with the

soil. Despite his near death experience, he’s kind enough to give us directions.

The road ends with a hairpin bend that leads to a red clay road, which ends at a

circular driveway with iconic gate posts. We wander up the red clay road through

a tunnel of green. There is a large, bamboo-hedged circle, which serves as a car

park. The front door is set in this hedge, making the house behind it quite

invisible to the first glance. A magnificent white bougainvillea conceals the

roof.

It’s hot and humid and we ring the bell over the garden door and the caretaker

appears. “Only 45 minutes,” he says. “Are you sure you want to spend 400

rupees?” “Right on,” I say digging into my pocket.

‘Brief’

The garden area is so vast that it is difficult not to get

lost and all the paths seem to lead to the front door. However, some of the most

beautiful spots such as the “hilltop lookout” with a single Araliya tree that I

have seen in so many photos are extremely difficult to find.

I ask politely for directions from the caretaker and add that we are from

paththaren (newspaper), to drive the point home. He guides us along the

perimeter path and leads us to a patch of greensward with a round pond set in

the middle. There is an enormous flight of stone steps to climb on to a hill

next to the pond. It is perhaps the most grandiose looking spectacle in the

garden.

The house

The house is minimalist. The floors are of bare cement, the

walls and ceilings are Spartan and without ornament. No signs of etherealness

and lavishness. Yet, this is a place of comfort and beauty. The house is full of

art, including Bawa’s own work and gifts from his friends, especially Australian

painter/sculptor Donald Friend. The sculptures of proportioned male nudes that

dot the house and garden stand out among many others.

Donald Friend stayed for more than five years in Brief during 1960s. Therefore

his art is strewen across Brief. Among which are a superb mural, which

represents Sri Lanka as the favoured isle of Hindu God Skanda, an aluminum

sculpture of Aphrodite rising, hides in a nook in the corridor. Terra-cotta

tabletops that bear Friend’s designs can be found everywhere.

No more a Garden of Eden

Nearly 80 years ago one man set out to create his own

miniature Garden of Eden and succeeded. However, as the caretaker of Brief Nihal

says things are gradually falling apart. “Before Mr. Bawa died, he distributed

his land among the villagers who served him. We did our best to look after the

garden. Yet, this is nothing compared to what it was.” From the dilapidated

outhouse to the statues that are being rapidly covered by rust, and the pathways

that are under attack by weeds show that Mother Nature is out to reclaim what

was once hers.

Sunday Times Dec

14 2008

The Bawas' Green Mansions

The famous Bentota

Gardens, Brief and Lunuganga – created by two famous brothers – are the subject

of a luxuriantly beautiful new book

By R. Stephen

Prins

In the ’70s, the

distinguished architect Geoffrey Bawa threw a big garden party at his sprawling

and celebrated home, Lunuganga. Taking his guests on a tour of his home and

garden, he made an expansive gesture that seemed to suggest the surrounding

countryside was an extension of his own grand property. Indeed, he was lord of

his domain and beyond, proprietorial about almost everything in sight, all the

way up to the green horizon. He then proudly told his guests about a small

correction he had recently made to the view.

“There was this

villager’s hut out there in the distance, and it had this hideous zinc roof that

got on my nerves every time I looked out of my window,” Mr Bawa was saying. “An

annoying little silver square squinting at me from that lovely sea of green.

Most aggravating. I could tolerate it no longer, so I sent my chauffeur over to

tell the house owner he would be doing me an enormous favour if he allowed me to

cover his roof with red tiles – at my expense, of course. He agreed, and we are

both happy!”

Like an artist

with a paintbrush, Geoffrey Bawa deftly smeared a dab of earth-tone colour over

a jarring metallic note and the tiny visual irritant in a corner of the canvas

was gone.

Lunuganga: Black

Pavillion

My mother was

one of the guests at that party 30 years ago, and she remembers Mr. Bawa’s

comment as one of many interesting things he said that evening.

The late

Geoffrey, like his brother the late Bevis, was an aesthete. Both men pursued

beauty with a passion, and both dedicated their lives to the creation of

beautiful things. Geoffrey designed houses, universities, hotels and resorts

that have become architectural classics, while Bevis dabbled in art and

sculpture and fashioned landscapes as a recreation and an occasional occupation.

And both men

have left behind what may well be their most widely appreciated and lasting,

certainly most evergreen, legacy – two flourishing, luxuriant artworks, the Bawa

gardens in Bentota.

Bevis spent 40

years growing and shaping “Brief”, the 2.5 hectare plot of land on the southwest

coast, north of the Bentota River, which was his home for the greater part of

his life. The landscaped grounds were also a source of income from the many

visitors who made a small contribution to see the famous garden. Brief became a

popular tourist destination, and attracted an assortment of visitors, from

Colombo residents to internationally famous writers, artists and royalty. It

continues to attract crowds, 16 years after the owner’s death.

Inspired by

Bevis’s home and landscaping venture, and not to be outdone by his older

brother, Geoffrey bought an even larger property on the other side of the

Bentota River, circa 1948, and laid out Lunuganga, a grand spread of a house and

garden worthy of one of Asia’s most respected architects and landscapists. Brief

is possibly the better known of the two gardens, because it was always an open

invitation to guests; Lunuganga was a private property that was opened to the

public only after Geoffrey Bawa’s death, in 2006.

“Though man

delights in destroying plant life, I have never known plants to let down man.”

BEVIS BAWA

“The garden had

grown gradually into a place of many moods, the result of many imaginings.”

GEOFFREY BAWA

Sketches of

Bevis and Geoffrey by Aubrey Collette

Both gardens are

the subject of a splendid new coffee-table book, “Bawa – The Sri Lanka

Gardens”, a publication that even seems overdue, considering the fame of the two

featured gardens and their creators.

With a text by

David Robson and photographs by Dominic Sansoni, the book is an extension of

previous related work by writer and photographer. Robson is the author of two

magisterial studies of the architect’s legacy (“Geoffrey Bawa – The Complete

Works” and “Beyond Bawa – Modern Masterworks of Monsoon Asia”), while Sansoni

collaborated with photographer Christof Bon on the black-and-white tome “Lunuganga”,

for which Geoffrey Bawa provided the text. The new book is the first major

publication to give prominence to Bevis and his beloved Brief.

It is all too

easy to overlook the text and focus on the visuals in a coffee-table book,

especially one as beguiling to the eye as this one. But the reader who skips

this text is missing out badly. There is much to enjoy and learn in David

Robson’s well-researched material, rich in detail and anecdote, and while the

content is scholarly, the writing is easy on the mind and pure reading pleasure.

As in a guided

tour with the perfect tour guide, the reader is gracefully led into the Bawa

gardens by way of two richly informative introductory chapters, the first

covering Sri Lanka gardens in general, historic and contemporary, and the second

telling the fascinating story of the men behind the two gardens.

By going back to the ancient kings who ruled from Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and

Kandy, and surveying the remains of royal palaces, and royal pleasure gardens,

as well as boulder gardens and monastic gardens, the writer shows how the stones

of Sri Lankan history have set a foundation for the Lunuganga layout. The widely

travelled Geoffrey was also influenced by gardens he saw during his student

years in Cambridge, England, and his visits to China, Italy, and Spain, among

many other countries.

Meanwhile, the

equally widely travelled Bevis, who started out as a planter on a rubber estate

in colonial Ceylon, was an admirer of the cosy interiors and picturesque

surrounds of the British planters’ estate bungalows that dot the hills of Sri

Lanka. This is reflected in the many charms of Brief.

Brief

The Bawas –

giants that they were in person, persona and talent – had a way of piqueing

everyone’s interest; curiosity about their work and life has always been high.

The second

chapter tells the colourful Bawa family story, and is generously adorned with

old family album prints and sketches and cartoons by artists such as Aubrey

Collette, Donald Friend and Bevis Bawa himself. The account is a fascinating

social history, going back to mid-19th century Ceylon, when Geoffrey and Bevis’s

grandfather, Ahamadu Bawa, married his French Huguenot wife, Georgina Ablett.

Entrusting the visual part of the book to Dominic Sansoni was a happy decision.

Not only is he possibly Sri Lanka’s most high-profile lensman, eminently

qualified to take on a project of this kind, he is also, through his family,

closely associated with the Bawas, and knows the two gardens intimately. The

Sansonis have been regular visitors to Bentota. The photographer has idyllic

childhood and teen memories of exploring the mossy wonderlands of Brief and

Lunuganga, packed with leafy secrets and arboreal delights. The Sansoni and Bawa

connection goes back almost seven decades. The photographer’s father Hilden

Sansoni was an officer in the Navy, while Bevis Bawa was a major in the Army,

and both took turns as aides-de-camp to a succession of British governors.

The

photographer’s mother, Barbara, along with the Australian artist Donald Friend,

designed a series of terracotta tiles which decorate a section of Brief.

Sansoni welcomed

the Bawa assignment. “My brief with Brief, so to speak, and Lunuganga was to

illustrate a text, a book about gardens,” Sansoni says. “Nothing more, nothing

less.”

Brief: East of

house Spanish court

There was also

the responsibility of doing justice to two people who were good family friends

and who held to the highest artistic standards. “I could feel the spirits of GB

and BB looking over my shoulder every time I used my camera,” he says. “Would

they approve, I kept thinking.”

Sansoni says the

Bawa brothers were as different as two siblings could be. Geoffrey was

formidably intellectual and reserved; many found his presence intimidating.

Bevis was genial, gentle, avuncular, a “darling man”. If they disapproved, the

responses would be markedly dissimilar. “If Geoffrey didn’t like something, you

knew it. There would be this Great Silence, capital G, capital S. If Bevis

didn’t like something, he’d let you know, but in the nicest way.”

It is hard to

imagine either brother faulting the impeccable, sumptuous and handsome treat

that Dobson, Sansoni and the Thames and Hudson publishing team have put

together. Leafing through the book, up in his study at the back of Barefoot (the

gallery-cum-shop-cum-restaurant-cum-hangout-cum-performing arts space that

serves as his alternate home), Sansoni relives the experience of working on the

project.

“It had a lot of

personal significance for me, of course. Geoffrey and Bevis were dear friends.

But this was work, and I was not aware of emotion or sentiment getting in the

way. The project took several months, and umpteen trips to Bentota. Often I

would stay overnight and start work early the next day, at first light.”

Light, or rather

the contrasting of light with shade, are uppermost in Sansoni’s mind when he is

prospecting for a golden photo moment. His preferred times for outdoors

photography are early morning and twilight, when the shadows are just about to

dissolve or congeal.

As we turn the

pages, he points to pictures that satisfy him: single and double-page spreads of

dappled vegetation, vistas of water and foliage and sweeping lawn shadowed by

trees and bushes, and glimpses of statues and paved paths, all seen from various

points in the two gardens and houses, with verandas, pillars, pergolas, loggias

and pavilions playing visually supportive roles.

Lunuganga: The

Broad Walk

“Contrast with

light and shade gives you a more three-dimensional image, and that depth invites

you into the photograph. I like the idea of the reader wanting to reach out for

a tree branch or enter the gardens and walk up a path.”

The interiors of

Lunuganga and Brief – filled with art, statues and gleaming antique furniture –

are also amply documented.

The writer

Michael Ondaatje once described the Bawa gardens as “self-portraits”. The

subjects of these dual family portraits are gone, but we will look at both men

as mirrored in the beauty of their work with nature, and we will continue to do

so as long as the gardens are cared for and allowed to flourish, and the

environment protected.“Bawa – The Sri Lanka Gardens” is a reminder of how

paradisal this country is. It is also a gentle nudge to the ecologically

indifferent who may forget just how fragile this natural wealth and beauty is

becoming.

by

Neville Weereratne

by

Neville Weereratne