World Trade-Centre where the Kaffirs were summoned

on roll-call

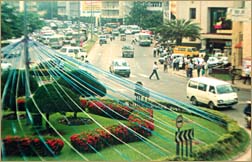

Regal Round-about where elephants roamed once.

by PADMA EDIRISINGHE Sunday Observer Feb 15 2004

|

|

The city of Colombo is today dubbed "The ultimate in our concrete jungles", not at all a complimentary term especially from an environmental point of view. But some four to five centuries back except for the little outcrop of trading settlements (mostly Moor settlements) around Kolon Thota, the area shared the characteristics of the average topography of our island as a showcase of lakes, waterways, marshes, shrubland and even small forests and hills of modest proportions.

Place names such as St. Sebastian Hill are indicative of the last gentry while place names like Madampitiya, Bambalapitiya were probably spawned out of groves of Maadam (a kind of juicy edible fruit even now growing in clusters by our streams) and Bambala (a name now not in usage).

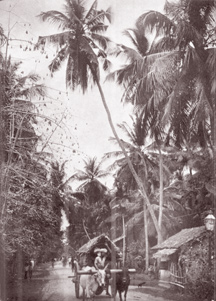

A forest spread evidently in the area facing Lake House today, a building sprouted centuries later out of the brains of the newspaper doyen D. R. Wijewardene who decided to baptize the magnificent mansion (by contemporary standards) The House by the Lake or Lake House. It was no doubt even then a rustic landscape exhibiting small settlements of humans and coconut plantations through which a waterway originating from the Kelani ran to the Indian ocean. It was this waterway and its branches that had catapulted to the Beira Lake that even today plays hide and seek all over the metropolis.

According to Dr. R. L. Brohier, by the Dutch period parts of this area had been transferred to coconut plantations and came to be known as the Buffalo's Plain. But that the jungle had yet retained its hold is testified by an incident related in "Changing face of Colombo" by the author (and translated to Sinhala by the writer).

According to the Official Diary of Colombo maintained by the Dutch on November 27, 1751 a huge black elephant had burst from the adjoining jungle and entered Colombo Fort through the Rotterdan Gate, now identified as the site of the Regal Theatre Roundabout. It had, in a mad frenzy of fury then wrenched off the arm of one sentry on duty and killed another by dashing him to death on the ground.

Forests, pachyderms on the run, gushing waterways - just 350 years ago that was the scenario around the present Regal Roundabout where the cinema hall that lent the place its name flashes its latest cinema pieces via giant posters and glitzy neon lights.

Meanwhile less gruesome things were happening close by in the 18th Century i.e. in the area where the tall Bank and hotel buildings and the World Trade Centre loom to the skies. It was no doubt another open space by the ocean where the ruling Dutch and the natives gathered for various purposes. After the British captured Colombo from the Dutch they had erected here five blocks of barracks for garrison troops in the year 1875 which complex came to be known as the Echelon Square. But before the capture the area had been known as the Kaffirs Veldt, a term it had earned later due to a hotch potch of turbulent events connected to the Kaffir labour force.

The initial import of Kaffir labour can be attributed to the Portuguese but the Dutch continued the import and soon they developed into a considerable segment of population within the Colombo Fort. Most of them worked as domestic labourers. Discontent that grew among them culminated with a "Kaffir insurrection" in which the Fiscal of Colombo and his wife were murdered at midnight in their bedroom by a Kaffir who worked in their household.

This catastrophe required a new system. Came the idea of roll-call before departure and on arrival where all Kaffirs had to answer a roll-call. From where were they to come and depart in the night? To the "lje" (island close by) that still retains the name Slave Island. Across Colombo's Lake (The Beira Lake) they were ferried to the lje. And where was the Roll-Call itself orchestrated? In that open space by the sea that soon came to be known as the Kaffir Veldt.

Today as you go about your business at the World Trade Centre or the high rise Bank of Ceylon building, just to ward off the tedium of it all in the blaze of scorching sun rays, you can visualise the rows of Kaffirs standing one behind the other and smirking as the Dutch officers true to the contemporary legend of White Supremacy lorded them over before they were led along a tiny passage through the ramparts to "Sallyport" for departure to lje, the jagged peninsula now also called by us, natives, Kompanna Vidiya.

Transformation of elitist neighbourhoods of Colomboby Rukshan Widyalankara, Chartered Architect - DN Thu Mar 18 2004

It was a day in the year 1505. According to legend several pale gentlemen appeared in Colombo, then a mere clearing in the dense maritime wilderness and asked the way to Cotte, the capital city of the kingdom.

Eventually directed to their desired destination by the most round about way possible, these gentlemen called "ferengis" by the natives belonged to a small European nation of considerable naval strength, called the Portuguese.

|

|

Galle Road then |

It turned out their mission was to "beg" the Singhalese king for a bit of land on which to build a church in return for which they would protect the Kingdom's coastal regions against invasions from the sea, for which purpose naturally a small fortress had to be built in Colombo. The king "granted" this request, the mission was accomplished and the first enclave of colonial power was established in Ceylon.

Three European nations colonized Sri Lanka. The power bases of these exotic white people from across the seas emitted a siren song, which seduced a considerable number of the native aristocracy.

Switching one's allegiance to the colonial power opened up dazzling vistas of power and riches of a grander scale than could be offered by any indigenous monarch. To the colonial power too, allegiance of the aristocracy was worth a great deal because it usually secured the allegiance of the commoners over whom the aristocracy held land tenure.

|

|

Galle Road now |

In this mutually dependent scenario the European settlers; the administrators, soldiers, prospectors, adventurers and merchants, together with their families were the original elite.

The original elite set the tune to which the indigenous elite moved. Life styles, dwelling patterns and architectural trends of the original elite became symbols of social exclusiveness to be adopted post haste by the indigenous elite. Where the original elite settled the indigenous elite eventually followed.

And so within the Fort of Colombo the first colonial elitist neighbourhood in Ceylon sprang up. Within resided the elite; people who got most of what there was to get; people who rose above the others in thinking, outlook individual abilities and perseverance; people who were trend setters and moulded the social changes in their time; people in whose hands reins of power were held.

Elite lived at the best locations, best addresses and best streets in town, aspired for social exclusiveness and used architecture to indicate status as well as to reinforce it.

They got most of what there was to get, rose above others in thinking, outlook, abilities perseverance, set trends, held symbolic or actual power and flocked together to form elitist neighborhoods.

During the Portuguese and early Dutch times the elitist neighborhoods continued to be confined to the fortifications.

The spatial arrangement of the Portuguese elitist neighbourhoods reflected the psychological instability of being continually under siege by the Singalese kings and latter by the invading Dutch.

Beginning from the 'Hill of St Lourenco and congregating around a number of churches of the Franciscan Order these neighborhoods symbolized nostalgia for the lost pleasures of 'Home'. "The nine hundred noble families that dwelt within the 3 mile long rampart invested this neighbourhood with characteristics of their hometown," noted Portuguese historian, Rebeiro, while king Sebastian of Portugal spoke fondly of 'My Cicada of Colombo'. Here as in the identical Portuguese colonial cities of Goa and Panjam of India, a sense of enclosure and proximity was achieved with the careful use of facades.

Then came the Dutch. Their elitist enclaves that were initially confined within fortifications but later spread out reflected the Dutch colonial policy.

The Dutch were great believers in blending with the native fabric as much as possible without compromising authority. Their architecture and town planning aimed at a close fit between the dwelling, the settlement and the environment. The result was a perfect symbiosis between the architectural traditions of the colonists and the colonized.

The Dutch fort Colombo through the eyes of Dr. Aegidius Daalman's, Belgian physician, "In the fort there are many respectable houses. Of which the house of the governor with that of the secretary, which is close by is very large and with its garden forms a complete square. Its front faces the seashore. The fortification serve as a road to the said houses... within the fort are many pretty walks and nut trees set in a uniform order. The streets are very wide with a beautiful row of trees on each side. Between them and the house is a very smooth regular pavement".

Soon the Fort was not enough and it became fashionable for the European, Ceylonese and hybrid elite to have addresses in Pettah, a fine densely built residential neighbourhood whose 'regularly planned streets intersected one another at right angles' to form a grid pattern that was reminiscent of a medieval Dutch town arrangement.

Talking about streets of Pettah; Main Street was 'the most graceful street in the world' but for some reason it was Maliban Street that was a fashionable promenade of the Dutch ladies; though one must remember that this was in 'the good old days when carriages were not wanted and Pettah enjoyed all the privileges of gentility'. Yet this 'neat, clean, regular arrangement' was regularly beset with flood problems, which one might say also gave a Dutch character to the neighbourhood.

In the close knit, interactive elitist neighborhoods of the Dutch era one often saw that, 'there was dancing and revelry within every other house'. Because open stoeps flanked it on both sides, the street, which was narrow and winding also became, 'alive with mirth and music' and appeared to be wider that it was.

The raised platform or the stoep which was an indistinguishable feature in the neighbourhood initially met the needs of a foreign and therefore isolated community to make a cohesive neighbourhood and later became a symbol of the princely hospitality dispensed at the indigenous 'Walauwwas' that stood elegant and detached in large plots.

The Dutch era saw the elitist enclaves spreading outward from Fort to Pettah and then northwards to the more hilly areas in Grandpass, Hulftsdorp, Wolvendaal and St. Sebastian Hill.

These north Colombo neighbourhoods established under the Dutch continued into the British era, but their days were numbered. Their subtle, unloud proclamations of elitism were not the order of the day for the British who were radical changers.

Traditional somebodyhood was upheld by the then ruling Dutch regime, and all status symbols including residences were unobvious, and blended into the indigenous fabric. British ended an era when those who moved up the ranks of somebodyhood were mostly somebodies to begin with.

Under the British sudden rise of individuals into somebodyhood was not uncommon and recent somebodies vied ferociously with somebodies whose somebodyhood was of a somewhat longer duration. The time had come to proclaim elitism loudly from gabled rooftops, ornamented facades and ornate gateposts.

However, more than these native factors it was the expectations of the British emigrants that gave the British colonial elitist neighbourhoods a unique architectural trend that was radically different from other eras. Britain in the 19th century was undergoing rapid industrialization.

Ugly chimneystacks emitting poisonous smoke were invading sweet English meadows and glens where elves and fairies once supposedly roamed.

The British settlers knew all too well and made sure that in Colombo the exact opposite happened. So it came to be that "in Colombo, with its rapidly growing flora of every tropical species the growth of a residential settlement transforms the luxuriant jungle into the more beautiful avenues and cultivated gardens".

Determined to preserve her better than elsewhere the rural spirit of Colombo in spite of the over dominating influence of the capital that elsewhere too often destroys it the British colonists set up their neighbourhoods.

They were initially attracted to the views of the port and outlook over the expanse of water afforded by the suburbs of Mutwal and Matacooly.

Elaborate and magnificent houses combining historic tradition with modern taste, comfort and convenience sprang up mainly along the sea belt in surroundings of true tropical charm.

Everyone of them; Rock House, Modera House, Elie House, Uplands and Whist Bungalow to name some, was truly a haven of peace and retirement where land spread over a ten acre ground with magnificent views: of the sea, the mouth of Kelani River, coconut grooves that stretch along the coast, picturesque fishermen's huts under coconut palms etc.

However, a port even in the fabled garden city of the East could not escape the ill effects of industrialization for long and when the surrounding environs started to become unhealthy, the elite defected to greener pastures. Cinnamon gardens and Colpetty in southern Colombo were in those days greener pastures in the most literal sense of the word.

Out of that thickly grown lush greenery emerged the pleasantest, most aristocratic portion of Colombo where houses of many wealthiest and most notable citizens were situated along canopied streets, where what met the eye was a labyrinth of pleasing leafy vistas flanked by imposing and charming dwellings of palatial proportions.

An evocative sketch of high life in colonial Cinnamon Gardens records 'Almost half past five O'clock.

The Galle face or 'Hyde Park' of Colombo begins to wear an animated appearance, there being many vehicles and horses in motion... The horses that draw vehicles, are invariably attended by their keepers, who run by the side of the conveyance... But no sooner is the sun gone down they all hasten home; partly in order to escape the fever laden evening air, partly to go through an elaborate process of 'dressing for dinner'.

Which brings us to the bungalow, the basic unit of Colpetty-Cinnamon Garden elitist neighbourhoods. What eventually became the bungalow was an early Indian dwelling type found mostly in rural Bangalore.

This was adapted by the British for their habitation in the colonies; keeping in mind 'first and foremost that it is the spirit of the British sovereignty that must be imprisoned in its stove and bronze while eastern features must be woven into the fabric as a concession to indigenous sentiment'.

The bungalow embodied the architectural hybridization that took place in all British colonies and was extensively used by the elite to exhibit and consolidate social dominance.

The horse drawn vehicles would enter through an ornate gateway set in a low boundary wall and move along a long dignified approach to the bungalow, which with its highly ornamented facades presented a controlled Victorian flamboyance.

A visitor looking out while being driven towards the spacious porch would be treated to the sight of the richly landscaped front-compound that often took up as much as 2/3s of the total compound and where fine trees grown quickly to great heights in this extravagant climate were planted.

Croquet lawns, tennis courts and well-kept green lawns too could be seen, where garden parties sometimes took place with guests seated on white wrought iron lawn chairs sipping cool drinks served by bare foot retainers dressed in white while the elaborate bonnets of the ladies enhanced the already picturesque scenery.

Even today, Cinnamon Gardens continue to be an elite stronghold. Nevertheless, about 30% of the imposing and charming dwellings of palatial proportions have become non-residential establishments and low boundary walls have been out of fashion for quite some time due to security concerns.

Instead of long driveways, the latest trend is to build almost up to the boundary, making for a totally encapsulated dwelling type with an internal courtyard.

Nor is Cinnamon Gardens big enough today to hold all the elite. Most of them have become resigned to the difficulty of getting land in this highly exclusive old money enclave and moved along Galle Road to the Havelock Town environs and even out of the city limits towards Kotte and Nawala.