NATIONAL

POST ONLINE – Oct-13-2001

Daddy

Sorebucks

http://www.nationalpost.com/search/story.html?f=/stories/20011013/734126.html&qs=lanka

Sir

Christopher Ondaatje has moved to London and given away millions. Is a

little respect too much to ask for?

The Daily

Telegraph

|

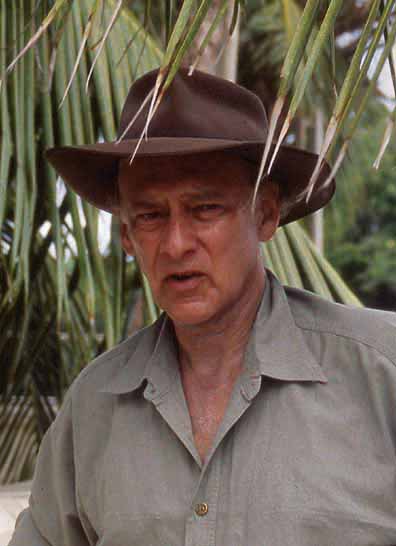

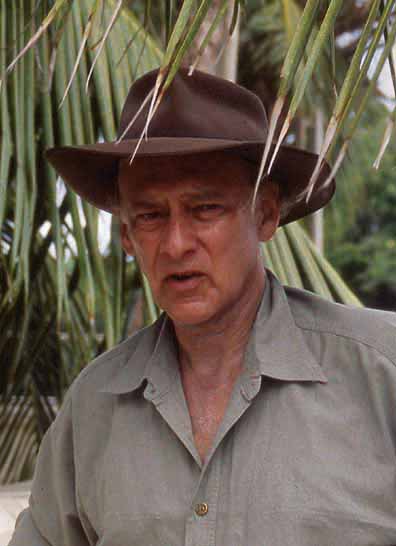

WHY CAN'T THEY LOVE HIM FOR HIS MONEY?: Christopher Ondaatje in the

Ondaatje Wing of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

|

Detail of portrait of Christopher Ondaatje by Daphne Todd, currently

on display at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

|

The philanthropist at home in Exmoor, England, December, 1998.

Ondaatje sold his company, Pagurian Corporation, and settled in

England for good in the mid-'90s. He no longer works as a financier.

|

|

The Tudor Gallery in the Ondaatje Wing of the National Portrait

Gallery;...

|

..., the Christopher Ondaatje South Asian Gallery at the Royal

Ontario Museum, Toronto.

|

|

In the morning room at the

Travellers Club, an exclusive establishment bastion in London's Pall Mall,

fire in the grate, sofas in groups around the walls, Christopher Ondaatje

appears. Dark-blue pinstripes, wavy grey hair, slightly tanned and aquiline

face. He looks at first as though he might belong here: patrician, elegant,

with a conscious conservatism and the long, supple body of the highly bred

Englishman.

He's been having lunch with

David Owen, formerly an MP for Plymouth in the southwest of England, now a

life peer. What did they talk about?

"Oh, you know, he wants

money for Plymouth," Ondaatje says. "It's something that needs hundreds of

millions of dollars, and, you know, it's not as easy to give money as people

think. You have to get involved, and I won't give money to anything in which

I don't get involved. I am not going to just give money away to satisfy

somebody else's ego. It's a lot of hard work. Plymouth is interesting. It's

incredibly tough but ..." This sudden rush of opinion, freely and openly

expressed to a stranger, with a head of emotional steam piling up behind it

-- that is not what usually happens on first meetings in the Travellers

Club.

Christopher Ondaatje is an

intriguing and enigmatic man: once a multi-millionaire financier who made

his fortune in Canada, then a major donor to the British Conservative Party,

now a funder of the Labor Party to the tune of more than $4.54-million;

elder brother of Booker Prize-winning novelist Michael Ondaatje, with whom

he has a tense and wary relationship; bobsledder in the 1964 Winter Olympics

and, more recently, explorer of the headwaters of the Nile; and for the past

decade or so, cultural philanthropist on such a scale that, as one Canadian

writer has remarked, "He has enough wings named after him to start an

airline." The latest in England is the Ondaatje Wing at the National

Portrait Gallery (NPG).

Ondaatje is 69, but his

body and manner belong to an angular, tensed teenager. I follow him around

the back corridors and basement of the club, looking for a room in which we

can talk. His legs don't seem to fill his trousers. He doesn't stroll as

club members tend to; he ranges along the corridors, shouting hello at

people in the offices whose open doors we pass, an untamed presence, wearing

the uniform of the accommodated. For some reason it occurs to me: Is this a

man in disguise?

We find a room with a

window and we talk. His speech veers from over-controlled, heavily

glottal-stopped packages to increasingly sudden, gabbling rushes at the

words, repeating the same phrase two or three times in a row, stumbling over

the syllables in a hurry to get them out, at times almost shrieking with

urgency. It is an extraordinary, unregulated experience. He may say he has

no idea how rich he is ("If you know how much you are worth, it isn't very

much. Anyway, I have given most of it away"); he may be the benefactor of

one vast cultural institution after another across the world; he may have

been made a Companion of the Order of the British Empire (CBE); but he

doesn't behave like that. He is clever, anxious, edgy and uncertain in a way

you would not associate with billionaires. Why is this man not more at ease

with himself?

It's worth remembering that

the Ondaatjes were once grandees in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, beginning in the

17th century. In their veins, as in many Ceylonese families, ran a mixture

of Sinhalese, Tamil, Dutch and British blood going back many generations. As

Michael Ondaatje has written, describing his own family, a friend of his

father's "summed up the situation for most of them when he was asked by one

of the British governors what his nationality was: 'God alone knows, Your

Excellency.' " His grandfather Philip Francis Ondaatje, a brilliant,

domineering, unscrupulous lawyer, had made them rich, buying up land from

peasant farmers in the highlands and selling it to the English tea planters.

Christopher's father,

Mervyn, although a charismatic man himself, remained in awe of his own

frightening, teeth-grinding father, who bullied him. Mervyn was driven into

spectacular deceit, gambling, wild bravado and drinking gin and tonics, from

which he never escaped. He held up trains with revolvers and once brought an

entire public procession to a halt in Kandy by throwing himself, in an

alcoholic frenzy, in front of the lead elephant. "A famous story," Ondaatje

says, not smiling.

Christopher, Michael (10

years younger) and their sister, Janet, loved their father and were appalled

by him, by the sourceless changes from bright-eyed, charming and hilarious

to a terrifying cloud of violence and threat. In those moods, as Ondaatje

says, "control, order, love -- everything went wrong. The whole family was

in disarray. We don't know what bloody devils drove him to drink, or

whatever it was that made him crack, but there was nothing worse. We were

kids. There was nothing we could do. My mother was destroyed by the

marriage."

Michael, in his

semi-fictionalized autobiography, Running in the Family, has run comic

threads in and out of this emotional anarchy, as if surfing the chaos on

which a writer can thrive but from which children cower. His brother has no

such ironic distance. Christopher treats his childhood as a sequence of

disasters.

His chaotic father, despite

his Dutch ancestry, believed more than anything else in the British ideal.

The family's servants were not allowed to speak Tamil or Sinhalese in his

presence, and when Christopher was 12 he was sent away to Blundell's public

school in England, where he was treated as a weird foreigner, with an odd

accent and sticking-out ears. His father then proceeded to drink the family

fortune away, so when Christopher was 17 he had to leave Blundell's because

they could no longer afford the fees.

His parents divorced,

despite Christopher's pleading letters to both of them, and his mother moved

to England, where she scrubbed doors in a Notting Hill boarding house. His

father died a violent and humiliating death, cracking his skull open on a

stone door while drunk. Christopher had left Ceylon five years earlier and

had not seen him since then.

In Christopher Ondaatje's

language, there is a constant drift toward the intemperate and a polarized

view of the nature of existence. "I have always identified with predators,"

he says. "In business or in the jungle, you are either predator or prey.

Since I didn't want to end up as prey, I had to become a predator."

Suddenly, as we are talking, he jumps up from the table and moves to

half-cower in the corner of the room. "Right now, for example," he says from

his corner, his long limbs folded in, remembering Blundell's but somehow

applying this to the whole of life, even to me asking him questions, "if you

argue with me and you shove me into a corner like this -- I was beaten down,

at Blundell's, right -- I would want to come out. I would want to talk to

you. I want to play rugby. I want to be good."

"Good" is Ondaatje-speak

for winning, for coming out on top, for not being prey. But there is

something else, rather more subtle, that lies behind it. "Good" also means

being accepted, feeling certain, knowing how the landscape lies, not being

"beaten down" by the forces of the world that will get you if you don't get

them. "Good" means feeling secure because you have won.

He was always clever, had a

brilliant eye for financial deals and understood early on that Britain in

the 1950s wouldn't give the necessary openings to a penniless Dutch burgher

from Ceylon. He left for Canada in 1956 and for nine years, "scratching and

clawing, twisting and turning," he struggled to establish himself in the

financial world. He married his wife, Valda, a Latvian chemistry graduate

from Dalhousie University, and almost immediately they had three children.

Over three decades, through a combination of stockbroking, publishing and

finance, he slowly acquired his enormous fortune on the back of the greatest

money surge the world has ever seen, the booming American bull market that

lasted from 1962 until 1987. Ondaatje rode that wave. "The world will never

see anything like it again -- not in my lifetime," he says.

But that world and that

financial success were not enough. Christopher has also written eight books

-- travel, political biography, one entitled Olympic Victory: The Story

Behind the Canadian Bob-Sled Club's Incredible Victory at the 1964 Winter

Olympic Games, as well as The First Original Unexpurgated Canadian Book of

Sex and Adventure (with Jeremy Brown) and The Best of Canadian Cooking. But

he hints that becoming an author has scarcely narrowed the gap between him

and his brother. "I've sold my soul to the Devil. I'm tough. I've gone

through fire and damnation. I'm tough, but my brother, he is an artist."

He decided to give up his

business life while on safari in Tanzania in 1988. When he bowed out of the

financial world, his company, Pagurian Corporation, was worth more than

$500-million and controlled assets, he says, of a billion or two, much of it

in cash. It was quite a sudden decision. "It was fun making the money, but

then what? Are you going to sit in the corner counting it?" He maintains

that he chose money as his métier simply as a means to an end. "I am not a

financier," he tells me for a second time, "I am a student of finance. And I

didn't choose money. I chose to be wealthy. It's very different. I chose

money because I wanted to re-establish my family. I wanted money because of

things I wanted to do with it."

He sold Pagurian and

settled in England for good in the mid-'90s. He no longer works as a

financier and is content to allow his money to make money. It took some time

for the financial world to let him go and for him to become detached from it

all.

All the time Ondaatje was

acquiring his fortune in the harsh and often compromised world of finance,

there was an ideal at the back of his mind. He would become a cultural

philanthropist in England. He would write more serious books (he has written

two on Victorian adventurer Richard Burton and is currently a little stuck

on another about Hemingway in Africa) and he would return to England and be

English. He quotes Sir John A. Macdonald: "A British subject I was born, a

British subject I will die."

Ceylon is a nostalgic

preface, Canada a long parenthesis in Ondaatje's life, but England is

intended to be the longed-for reality, the home the often brutal, thin-ice,

virtual world of Toronto finance could never be.

"I have invented myself

several times," he says. "When I came to England, I had to invent myself at

school. When I went to Canada, I had to invent myself. Came to England again

and I completely had to reinvent myself. You are not talking to me now as a

financier. I am where I want to be and I am what I want to be. If you are a

financier, you are a selfish person. You are there to make money, to do

whatever you have to do to make money. The paper world is a false world. It

is an intangible. I don't have to do that any more. I am real."

The long experience of

uncertainty continues to boil inside him because the country he has loved

from afar for so long is now treating him as if he were a new boy at

Blundell's, with his olive skin and his complex accent. "I love Canada and

all that kind of stuff, but I'm British, and to do a thing [in Britain] that

is really worthwhile is really fantastic."

Why more so than in Canada?

"It just is. It is harder

to do. You can't just do anything you want in [Britain]. It is just the way

it is. This is an older society. Canada, you do it on the back of a matchbox

and stuff like that. Not here. You have to go through various channels.

There is a board that has to accept you. They don't know if they should do

it with you or not."

He begins to talk about the

National Portrait Gallery, where the new $36.28-million Ondaatje Wing, a

beautiful and sleek piece of squeezed-in Modernism by Sir Jeremy Dixon and

Edward Jones, was set on its way by a key early donation from Ondaatje of

$6.25-million. His money enabled the gallery to receive the all-important

matching lottery funding. He has given and given and given -- to the Royal

Society of Portrait Painters, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Victoria and

Albert Museum, the Royal Geographical Society, Somerset County Cricket Club,

Blundell's, the Bermuda National Gallery, Dalhousie University, the Art

Gallery of Nova Scotia, the National Ballet School of Canada, Massey

University in New Zealand. But the beautiful NPG wing is his proudest

achievement.

Here, though, the habits of

the "old society" have come devastatingly into play. In Ondaatje's mind, or

at least as he speaks to me, those habits are concentrated in the figure of

Henry Keswick, former owner of The Spectator, Conservative Party grandee and

chairman of the National Portrait Gallery's trustees. "I like Henry Keswick,

but I like him from afar and I certainly think that, if he likes me, he

likes me from afar. I never felt that I was part of him."

That's Tory grandeedom,

isn't it?

"You said that, not me. The

people whom I have worked with are the director of the gallery, Charles

Saumarez Smith -- I have a very good rapport with him -- and Chris Smith,

the secretary of state, a very warm, understanding person. But I made it

work. My involvement made it happen. I was the catalyst. But I'll tell you

something: My name was kept in the dark for 4 1/2 years. I made my offer to

them, and no one knew about it for 4 1/2 years. It's OK. I don't care.

Afterwards it was OK. Henry Keswick had his reasons."

What were they?

"Listen, I'm not going to

get into all that. I learned a lot over those 4 1/2, five years. For

somebody like me, who is free enterprise and a go-getter, who has lost

everything, who builds himself up in North America and then comes here,

there's a different set of rules. Just the same as when I'm coming to

school, coming to Blundell's at the beginning."

Then, suddenly, he is

angry. All the pinstripe nonsense falls away. "You are not going to

discourage me. You are not going to beat me down. I don't care about the

biases and I don't care about the bigotry, it doesn't bother me."

You recognize it, though.

"I recognize it and I have

dealt with it."

And it is an absolute

reality?

"Absolutely, absolutely."

I ask him how he came to

make his $4.54-million donation to the Labour Party. The sequence of events

is as follows: Lord Levy (Labour's chief fundraiser) asked him to make the

donation in November of last year. He agreed in December, and the money was

transferred in early January and then announced.

"What is best for the

country? I am 69 years old. If I am going to do anything for real in this

country, I am not going to back a bunch of losers who are divided, who have

no ..."

You have been Conservative.

"Absolutely, and I have

sponsored the Tory Party, too, given money. Don't ask me how much -- quite a

lot."

Comparable amounts?

"No, nothing like. But I've

given it to senior people, and they just take it in an arrogant fashion.

They are not interested in me. They are not interested in me or anybody like

me. But more than that, I am sick to death of being beaten around, called a

foreigner, and used, with this bigotry or whatever it is ..."

So here it is, nakedly and

straightforwardly expressed: Christopher Ondaatje's $4.54-million donation

to the Labour Party for its general-election expenses was made because of

his loathing for Conservative xenophobia, snobbishness and exclusiveness. I

put those words to him.

"You are saying this, not

me. Those are not the words I would have used ... I tell you that, with all

of this, suddenly I realized that the politics of aspiration, the politics

of achievement or the politics of attainment or the politics of reaching a

second or third social level, that is all very well, but at some point in

your life you have got to clear your head and you have got to tell the

truth, the real truth.

"It happened quite

suddenly. I have had some very good relationships with senior people at the

Labour Party. Michael Levy -- Lord Levy -- came to see me. A nice guy,

absolutely straight. He was the catalyst. I met Blair and one day I went

back to my wife and said, 'Y'know, sweetie, they want me to give them a

hand.' And Valda said, 'Why would you do that?' And I said, 'Well, you know,

this is different now, the country is different.' Here is somebody telling,

I felt, the absolute truth, that he really wants to remould the welfare

state, which could well be bankrupt, and he wants to remould that and start

making, if you like, a new political party, and he wants to do something for

this country, and I believe him."

What about the peerage?

"No, sir."

Would you take one if you

were offered one?

"No. It does not fit. It

doesn't fit."

You took a CBE happily

enough.

"I think that is completely

different. I must tell you truthfully that it was never discussed. There was

never any promise made, there was nothing ever asked, nor did I ask."

No hints dropped?

"Absolutely none."

Clive Soley, or was it

Chris Smith, called you Lord Ondaatje by mistake.

"No, he didn't. It was

never discussed. I don't think a peerage fits with me. Seriously, it was

never an ambition of mine."

But you are a patrician man

...

"Never discussed, never

discussed, and I don't think it should be discussed either."

All right.

"It was never discussed. It

is not one of my ambitions."

Would you refuse it?

"I'll think about it then,

if I am ... I don't think I want to be a working peer. That's important.

It's different now. To have some damn title and do your grouse shooting is a

completely different thing. It's not me, you know ..."

No, I can see that.

"Do you know what you

should ask me? Your last question?"

What?

"You should ask, 'What is

your biggest disappointment?' "

OK. What is your biggest

disappointment?

"If I was really to tell

the truth, my biggest disappointment is not being invited to be a trustee of

the National Portrait Gallery."

I agree that it is

scandalous that he hasn't been. Nine trustees have been appointed over the

past three years, including historian David Cannadine, biographer Flora

Fraser, Tessa Green, chairwoman of the Royal Marsden Trust, artist Tom

Phillips and Vogue editor Alexandra Shulman. It is not grandeedom or status

that Christopher Ondaatje is after, but something simpler and deeper than

that: acceptance, a kind of absolution. That is what all his gifts are

asking for.

An ANCHORMAN

Exclusive Oct 2005

By Dirk Tissera

CHESTER, Nova Scotia - After twenty long years ‘on and off’ and more than 16

visits to the Island, Sri Lankan-born knight, Sir Christopher Ondaatje 72,

‘signs off’ with an absorbing literary masterpiece - “Woolf in Ceylon” - an

Imperial Journey in the Shadow of Leonard Woolf 1904-1911

“It is my last book definitely and certainly my best,” Ondaatje told The Sri

Lankan Anchorman in an exclusive interview from Chester, Nova Scotia this month.

Woolf in Ceylon hit the book stands on October 1, 2005 in the UK and Ondaatje’s

insight and compelling commentary on the life and times of Leonard Woolf

combined with a powerful blend of historical pictures, is a keepsake every Sri

Lankan should possess. In this book, Ondaatje writes from the heart.

See also

“You will see that

there are a lot of similarities between Woolf and myself – even though we were

born over half a century apart. “After a decent English education, each of us

was shipped off to another country to make our own way. Woolf to Ceylon (where I

was born) and I to Canada,” Ondaatje says with a quiver in his voice.

“Both of us made a considerable success of our careers – but each of us then

gave everything up to concentrate on publishing and writing. (Also anyone who

reads Woolf in Ceylon will realize – both of us were ‘outsiders’ and had to

learn the game of hard knocks.”)

Woolf in Ceylon is not just a travelogue. It is a very personal biography as

well as a literary critique of Woolf’s (literacy) in Ceylon.

Business interests

Christopher Ondaatje, is amazingly the only person who took the trouble to

research and go into Beddegama (a jungle today), after Woolf wrote his first

novel, the best selling Village in the Jungle, which was published in 1913.

Ondaatje’s exploits are many, both on the business and sporting field. From the

late 80s to early 90’s - he sold all his business interests and went back to

writing, where he broke new ground as a respected book reviewer and a writer of

thought-provoking books - dealing with significant biographical, historical and

geographical events.

He was named an Officer, Order of Canada in 1993 and has received three LL.Ds.,

honoris causa, one from Dalhouise University in 1994, the second from the

University of Buckingham in 2003, and a third from Exeter University in 2003. He

was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the Queen's

birthday honours list, June 2000, and awarded a Knighthood in the Queen's

honours list, June 2003.

Ondaatje was a member of Canada’s 1964 Bobsled Team (Thrill Seekers). The team

comprised, Vic Emery, Lamont Gordon, John Emery, Charles Rathged Jr., Peter

Kirby, Chris Ondaatje, Gordon Currie, Dave Hobart and Doug Anakin. They won a

gold medal in the four-man competition at the Commonwealth Games and captured

Canada’s only Olympic gold medal of the 1964 Games. It was Canada’s first gold

in bobsledding.

“We trained at Lake Placid for the Olympics,” recalls Ondaatje of that golden

era.

Ondaatje basks in glory and enjoys a reasonably ‘quiet and sedate’ life in

England today. “I am in real good shape and feel much better than 10 years ago,

he says. I have no health problems and I keep myself fit.”

Ondaatje married his Latvian wife, Lady Valda in 1959. He met her in Montreal.

He started off his journalism career working for a Montreal magazine selling

advertising and wrote a column for the Financial Post later.

He has three

children, David 45, who is a script writer in the Hollywood movie industry,

Seira 43 and Jans 41- and twelve grand children.

The former

millionaire businessman and now modern-day explorer and writer and patron of the

arts, left Sri Lanka in 1947 to go to school in England - Blundell's School in

Tiverton (1947 – 1951). He worked in the City of London and emigrated to Canada

in 1956. He is a keen follower of cricket, tennis and sailing.

Ondaatje played cricket representing the United Bank in the UK. He also played

rugby and was involved in athletics. When in Canada he played cricket for the

Toronto Cricket Council. In Sri Lanka he studied at St. Thomas’ Guruthalawa.

Ondaatje made his

fortune in publishing and now administers his own charitable foundation and

actively supports a number of UK organisations. He is the benefactor of the

National Portrait Gallery, where the $36.28 million new Ondaatje wing named in

his honour, was opened by the Queen in 2000.

“When I left Ceylon in 1947 I never saw my father again,” Ondaatje says with a

lump in his throat. His father was an alcoholic and died when he fell and

crushed his head on a stone. “I saw my mother after five years.”

Perhaps those were the years which drove Ondaatje to be the person he is today.

“I’ve accomplished my dreams.”

Politics was never

Ondaatj’e cup of tea. “I did not have interest in politics,” he says adding: Sri

Lanka has too rich a culture to be engulfed in petty politics.”

An emphatic “NO”

Asked if he will someday decide to go back and reside in Sri Lanka - Ondaatje

responds with an emphatic “NO”.

Woolf in Ceylon is

surely one of Ondaatje’s best books, although the Prime Ministers of Canada sold

over 600,000 copies and Journey Source of the Nile reached 400,000. His other

books are: Hemingway in Africa, Olympic Victory, Leopard in the Afternoon, Sindh

Revisited and Man-Eater of Punanai Meanwhile, the Cambridge Society in the UK is

joining forces with the Ceylon Bloomsbury Group to present a day of fascinating

talks built around the book The Village in the Jungle by Woolf, founder of the

Hogarth Press.

A recently-published edition, revised and annotated by Yasmine Gooneratne,

restores the book to its original and unexpurgated state. The conference will

explore the contribution Cambridge graduates have made to the literary culture

in the UK and abroad. It will hear about the influence of the Bloomsbury group

on writing in the UK and about Ceylon in the period when Woolf was writing.

Speakers will

include Victoria Glendinning, who is writing a book about Leonard Woolf, and

Ondaatje.

Sir Christoper and Woolf may have similarities …but Ondaatje does not seem ready

to cry Woolf just yet. “History of Paper will most surely be my last book.”

- Christopher Ondaatje’s new book Woolf in Ceylon: An Imperial Journey in the

shadow of Leonard Woolf 1904-1911 is published by Harper Collins and will be

available in the United Kingdom on 1st October.

Sunday Times - Nov 27 2005

COMING BACK TO

THE LAND HE LOVES

He looked east to his much-loved Ceylon from which he had been “wrenched” out as

a boy and then looked west towards Canada and made a simple decision. That

decision taken in London, as a callow youth yet with an incisive mind, was the

turning point in his life.

More than half a

century later, this multi-millionaire financial wizard now retired from the

corporate world, and indulging in his passion for travelling, adventure and

writing, sees it as a “good economic decision”.

Who is this

enigma, who prefers coconut arrack to palmyrah arrack, considers rice, curry and

tilapi “a first-class dinner”, enjoys a hot wild boar curry; is equally

comfortable being knighted by the Queen of England as he is gazing at the myriad

stars over the ancient city of Anuradhapura or gingerly stepping across

heavily-mined areas to photograph the scarred shells of buildings or

island-hopping off Jaffna; or tracking a sleek leopard at Yala? What has made

him what he is today?

This is what we

attempted to find out when we set out, albeit with some trepidation, to meet

Christopher Ondaatje, whose brother Michael, author and Booker Prize winner, is

more familiar to Sri Lankans with the award of the annual Gratiaen Prize in

memory of their mother.

Before the

interview a frantic search on the net gives only a sketchy description about

Christopher Ondaatje…….born in colonial Ceylon, educated in England, made his

money in Canada from banking, finance and publishing, retired from the corporate

world in 1995 and now travelling the world. A few clippings from local

newspapers in the 1990s focused on him briefly when he bought Forbes and Walker

through the Ondaatje Corporation.

An insight into

what is closest to his heart, however, comes out in Ondaatje’s latest book:

‘Woolf in Ceylon -- An Imperial Journey in the Shadow of Leonard Woolf

1904-1911’ where he retraces the footsteps of Woolf, 100 years after him to his

haunts in Jaffna, Kandy (even Bogambara prison where after the visit Ondaatje is

advised to wash his hands with carbolic soap to ward off scabies) and Hambantota.

Through its pages, the reader also gets a chance to look into Ondaatje’s own

life and love for this land.

Ondaatje, who

turns 73 on February 22, himself sets the tone for our interview when we meet

him at his sister’s elegant home in Nawala last Monday. He is in Sri Lanka for

the ‘celebration’ tomorrow of his book on Woolf, well-acclaimed both here and

abroad.

With a warm

handshake and an enigmatic smile, he puts us at ease, in his own suave manner

while taking time to pat his sister’s dog, Hector. Ondaatje’s own life seems to

be the stuff stories are made of. The eldest son of a wealthy family of Dutch

origin, his early childhood was idyllic. Born in Kandy, he lived his early life

on his father’s tea estate at Pelmadulla, schooled at St. Thomas College,

Gurutalawa and briefly at Breeks Memorial School up in the Nilgiri Hills in

India. Most of all what is etched in his memory are the many journeys made to

different parts of the country, including stays at Taprobane (earlier known as

Count de Mauny’s island), the tiny isle off Weligama in the south and also

forays into Yala, nurturing his fascination of leopards.

“I love leopards,

most people do,” he laughs when we query whether this love is linked to him

being dubbed one of “Toronto’s most aggressive and predatory businessmen”. His

explanation is…..“in business there are only winners and losers, no halfway.

Those who are selfish and unselfish…..if you go for what you want then you are

considered to be selfish”.

“As a young boy,

life was wonderful and wild…….sketching birds, collecting birds’ eggs,” he

recalls. It was not to last, however, and reality struck all too soon, when he

had to leave the land, the life and the people he loved. Didn’t he have an

option? “You do what your father tells you,” he says.

The heartbreak

comes out in his book when he writes: “I am thrilled by Yala partly because I

connect it with happy memories from my early years. When I was still a boy my

father took me on a trip around Ceylon for a fortnight by car. The year was 1946

and I was twelve. It was probably the highlight of my life until then, and it

was certainly the last thing my father and I did together, just before we were

separated for ever.” He never saw his father, Mervyn, again.

Ondaatje was off

to public school in England and a completely different life. “You had to learn

to be an Englishman……….new school, new rules and new lessons. Thank God there

was cricket, a passion with me.” He sees cricket as the redeeming factor,

helping him an “outsider” to integrate into this environment at Blundell’s

School in Tiverton, Devon. Later in Canada he would be part of the bob-sledding

team sent to the Winter Olympics of 1964.

More trauma dogged his youth, money and family troubles far away in Ceylon that

would have a permanent bearing on his life, for his father had a drinking

problem. Penury stared them in the face, the family, which had wined and dined

at such places as the Queen’s Hotel in Kandy during those colonial days, was

destitute. Ondaatje without a means of completing school, started work in the

city of London at the National Bank of India, expecting to come back to Colombo

as an Assistant Manager.

By this time his

mother, Doris, too had come over to England, making a break with his father.

“Mother was an incredible woman. When things collapsed for us she had made the

decision to leave my father and come out to England with no money but just to be

with her children. She took a job in a boarding house, running the place in

exchange for a room in the basement she shared with my sister Janet and a tiny

little triangular room in the attic which was my room. We were poor but my

mother would explain to us that although we were living in Chelsea with the

Bohemians we were the real Bohemians. We were the people who had lost or given

up everything and we were living the Bohemian life in London. She gave us

incredible confidence. When we walked out of the house onto the street we

considered ourselves aristocrats and princes. It is her confidence, stamina and

sense of drama that stuck with us. Somehow we survived and somehow we lived and

learnt and wrote about it particularly Michael,” he says. His other siblings are

sisters Janet and Gillian in between himself and Michael and Susan.

A tinge of

sadness creeps into his voice as he speaks of his father who loved him dearly

and whom he loved deeply. “He had a drinking problem and he was a tyrant. His

world collapsed when I left for England and my mother divorced him. His family

was his life and he was left a broken man. He had quite a sad death in Kegalle.”

Throughout this

turbulent period in his life Asia was also in transition. The British Empire was

on the wane. Looking east Ondaatje saw the business of the bank he was working

for and other eastern banks, the wealthiest in the world, “disintegrating right

under my eyes”. From 1962-1987 were the fastest growing years in North America

and Toronto was the fastest growing city there and his gamble to head west in

1956 paid off although in later life after he had achieved his aim of making

money, this hard-nosed tycoon urged the west in the 1990s to look east towards

Southeast Asia for new economic frontiers.

His youth was

dedicated to working hard, his sights set on breaking into investment

particularly stock-broking to “rebuild my family fortune by hacking my way into

corporate finance”. This was also the time, in 1959, he married Valda, his

Latvian wife. They have three children and 12 grandchildren, says Ondaatje, very

much the family man. Son David is in California, daughter Sarah in Connecticut

and youngest daughter Jans in England where he and his wife also live. Is Valda

with him on this trip to Sri Lanka? “No,” he smiles, “she is enjoying a rest

back home.”

1961 was the year

he read Woolf’s autobiographies published in five volumes, the second of which

was ‘Growing’. In those “unputdownable” pages, he was reading about the Ceylon

that he knew and loved. “Imagine my surprise,” he says and with it came the

resolve to write about this man (Woolf) and about Ceylon much more than he had

done, for he had left out such integral areas of the country as Anuradhapura,

Polonnaruwa, Dambulla, Sigiriya. “He hardly talks even about Colombo…..Not the

caste system……Inadequately dealing with Kataragama and does not use the word

mudaliyar.”

With humility,

Ondaatje explains he had to “learn to write”, adding, “in Sri Lanka we are

taught very well. English is taught well”. The task before him was to learn to

write, complete the research and to get credibility not with just one book but

with several. And like in all of his other ventures, he says that’s what he has

done. The seven books he wrote before Woolf include ‘Olympic Victory’, ‘Journey

to the Source of the Nile’, ‘Hemingway in Africa’, ‘Leopard in the Afternoon’

and ‘Man-eater of Punanai’ which he says sells even now.

If he had his life to live over again, any changes he would wish for?

“Not gone into finance to make money in selfish business. If we had the money

and kept the money, I would have started earlier…I’ve been writing and exploring

only for 16 years…but then I would have started earlier. First I would have

liked to go to Cambridge and then later done real exploration for the Royal

Geographical Society….as opposed to writing about my heroes one of whom is

Leonard Woolf, a remarkable man.”

He first gave in

to the lure of Sri Lanka only in 1990. Though the corporate burdens were still

heavy, he came back and picked up the pieces of his childhood which resulted in

the book about the man-eater. Since then the country of his birth has seen him

pay at least one or two visits every year. A holder of British and Canadian

passports, with many an honour bestowed on him in both of these adopted

countries, and indulging in the pursuits of the rich such as golfing, sailing,

travelling and photography, he says, “I keep coming back because this is my

country and I am very much at home here. What I’m doing is living the life I led

before I left Ceylon. Within a day or two of being here, I am off in a jeep with

a driver into the jungle. Ask anybody, any expatriate, it is the thing they miss

most……that and cricket.”

How many get a second chance like this, he muses. “Dabbling in corporate finance

was fine but this is fantastic,” is how he describes what “chucking up business”

has done to him. “I feel 10 years younger. It is immensely satisfying and

enjoyable.”

Tentatively we

query what he has done for this country. Yes, we’ve read about all the

philanthropy, the National Portrait Gallery in the UK naming a wing after him

over his contributions, Ondaatje becoming part of the exclusive club of the

Labour Party’s ‘million plus’ and the Ondaatje Fund which fosters the

development of learning and international understanding.

“No, I do not

want to award a literary prize because I don’t want to step on Michael’s toes,

he is my brother. There is an Ondaatje Bungalow that I built in Yala to help

reduce the poaching and for better policing of a certain area which seemed

unprotected. This is to do with my great love,” smiles Ondaatje.

His fondness for the country is evident in the quote that sears our very being

as Ondaatje concedes: “You can take the boy out of Ceylon but it is not easy to

take Ceylon out of the boy.”

Ondaatje

on Woolf and Jaffna

Christopher Ondaatje has used Leonard Woolf as a shadow behind which to make a

social commentary of a hundred years of Ceylon’s and Sri Lanka’s history. “It’s

not just a biography, it is also a travelogue and involves literary criticism

and a social commentary not just of the present day or Woolf but about

independence, post-independence, 1972 name change and about the escalation of

tensions between the Sinhalese and the Tamils.” “Frankly the metamorphosis from

Ceylon to Sri Lanka has been a turbulent journey,” explains Ondaatje.

“I worked hard at

it and used two props……the travelogue or safari and photos, 60 in all.” The

super photos in the book include some which he himself clicked braving mines and

all and others he found rummaging through boxes and boxes at the archives of the

Royal Geographical Society in England. “These photos were taken during Woolf’s

time in Ceylon and have never been seen before.”

Leafing through

the book he picks out two “fantastic” pictures – ‘Street scene, Colombo, around

1905’ and ‘Village crowd, Ceylon, 1910’.

When asked for a comment on Jaffna, which he visited in March 2004 in the

footsteps of Woolf who was posted there in 1904, this is what Ondaatje says,

“The world has a different view of Jaffna than it actually exists. In fact,

Jaffna is very much a part of Sri Lanka and when you travel in Sri Lanka

researching the book, if you can ignore the checkpoints and the military and the

militant attitudes of the people paid to be militant, the people of Jaffna and

the people of the south, basically the Tamils and the Sinhalese are very much

the same islanders who are fed up with the war which is disturbing the normal

way of life.

“Everybody talked

about it in Jaffna. People were incredibly kind and friendly but it was

impossible to ignore the devastation I witnessed around me: Elephant Pass fort

no longer in existence, the churches, almost rubble, the kachcheri where Woolf

worked just a ruin now and the magnificent old Jaffna fort merely a shadow of

its former glory with only its scarred perimeter still standing.”

Another book in

the offing? Though Ondaatje has vowed that Woolf will be the last and he will

cry halt, only time will tell.